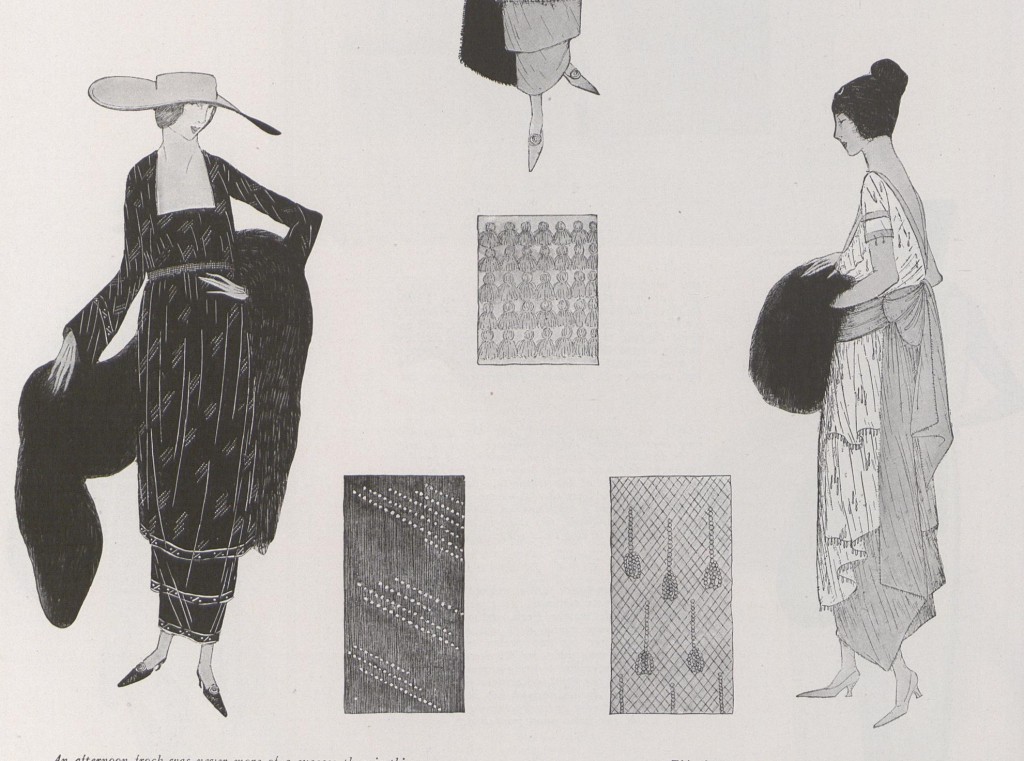

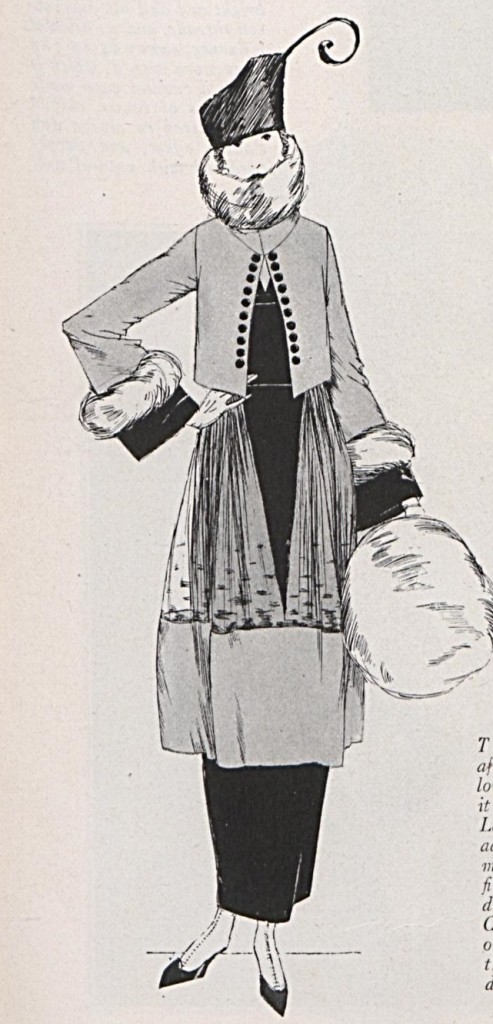

The recent exhibition at Tate Britain, ‘Now You See Us’ highlighted the achievements of women visual artists working in Britain over 400 years and more, both known and unknown. The exhibition was keen to include techniques other than figurative painting, featuring calligraphy by Esther Inglis and botanical paper collages by Mary Delany. However, with its focus on works made for exhibition (framed oil paintings, or botanical watercolours reproduced as prints) it omitted an important avenue for women’s work, their commercial art. Made as outline drawings, with some shading, this was used by retailers in newspaper advertisements and sales leaflets promoting clothing and furnishings. While functional and apparently lacking in creativity, this work offered a route to employment for women artists. The boom in women’s magazines from the 1880s onwards created a demand for ‘fashion artists’ who had some understanding of clothing design and construction if not necessarily of human anatomy (problematic for women who were excluded from life drawing classes). The growth of this profession is reflected in the number of people describing themselves as ‘fashion artists’ in the Census: 6 in 1891, 83 in 1901 (70 of them women) and 364 by 1911 (324 women).

The most prominent British ‘fashion artist’ of the 19th century was Adelaide Claxton (1841-1927), who, with her sister Florence (1838-1920) started her career as a fine artist, exhibiting at the Royal Academy and the Society of Female Artists during the 1850s and 1860s. The sisters also wrote and illustrated humorous articles for periodicals like the Illustrated London News. Florence married in 1874 but was the main breadwinner: in the 1881 census her husband described his occupation as “managing his wife’s business.” During the 1880s Florence established herself as a leading fashion artist, drawing images for all the major London retailers and for others in the provinces. Her work was so prolific that it dominated the pages of leading fashion magazines like The Queen. While Adelaide had a purpose-built house and studio in the artistic suburb of Bedford Park, Florence struggled to support herself as a fine artist, dying alone and impoverished.

(Copy 1 66/329, 1884 The National Archives)

Adelaide may have been a role model but she was far from typical. Very few of the ‘fashion artists’ listed in any of the Censuses were married, and most of them lived either in shared lodgings or a family home in unglamorous suburbs. For example in the 1911 Census the Martin family of Hendon comprised four unmarried sisters, a milliner (age 39), a dressmaker (33), and two fashion artists (29 and 26). One of the few married ‘fashion artists’ in the Census was Mrs Fazan of Putney, whose husband and eldest son were listed in 1911 as ‘photo engraver’, while her three daughters aged 15-17 were ‘art students’. By 1921 the three Fazan daughters were also ‘fashion artists’ and their younger brother was an ‘apprentice photo lithographer’. All of the Fazan children were still unmarried although well into their twenties.

As ‘fashion artists’ often worked freelance there would be no rules preventing them continuing after marriage, but the work may not have been worthwhile for women trying to juggle housekeeping and childrearing. Articles adressed to aspiring ‘fashion artists’ warned of the long hours and physical effort required to capture fashion trends: “She must be very rapid in sketching, and she must have plenty of physical endurance. At special seasons when a great many shops and workrooms have to be visited in hasty succession, and hurried drawings made in each, the work becomes a heavy strain.” (Northampton Mercury, 3 January 1908). There was also the difficulty of negotiating payment in a buyers’ market, with fashion artists too often “glad to sell drawings which have taken hours to work up for five shillings each”. Readers asking for advice on training were warned that it was best to go to an established art school rather than paying for an apprenticeship to a fashion artist who might not provide any useful contacts for employment.

Notwithstanding these challenges, the work does seem to have provided a living for women with a background in fashion or in draftsmanship. The National Archives contain hundreds of drawings of garments signed by female fashion artists between 1880 and 1900, and a close reading of women’s magazines and newspaper columns suggests that there are thousands more images that could be linked to named artists. Newspaper reports on the prizes awarded by the Female School of Art name recipients, including Ellen Ashwell who went on to make a career as a fashion artist. Further research in the records of art colleges is needed to show how they provided training for fashion artists, and to what extent this was a chosen path rather than a backstop.

- ‘Copyist or creative? The emergence of the woman fashion artist in Britain, 1880-1920’, Journal of Design History, 2024 https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/epae012